From The Inside Out: Transformative Education in Bolivia

““If the structure does not permit dialogue, the structure must be changed.”

Paulo Freire

Cochabamba, Bolivia

Back in the village of Pinuya in Acre, community teacher Amanda told us of the difficulties of balancing the need for younger generations to hold onto their Huni Kuin language and culture, whilst also preparing them for the wilder world. But despite the challenges, at least she has some control over the curriculum. In other parts of Brazil, the situation is far more troubling. Thought by many to have taken their place in the past, so-called ‘factory schools’, which aim to ‘reprogramme’ indigenous children to conform to the dominant culture still exist in many states. Bewildered indigenous youths, disorientated about their pasts and futures, as are systematically denied their history and identity. We can’t build inclusive and innovative systems if children are merely being taught how to be cogs in a machine. Democracy needs to start in the classroom.

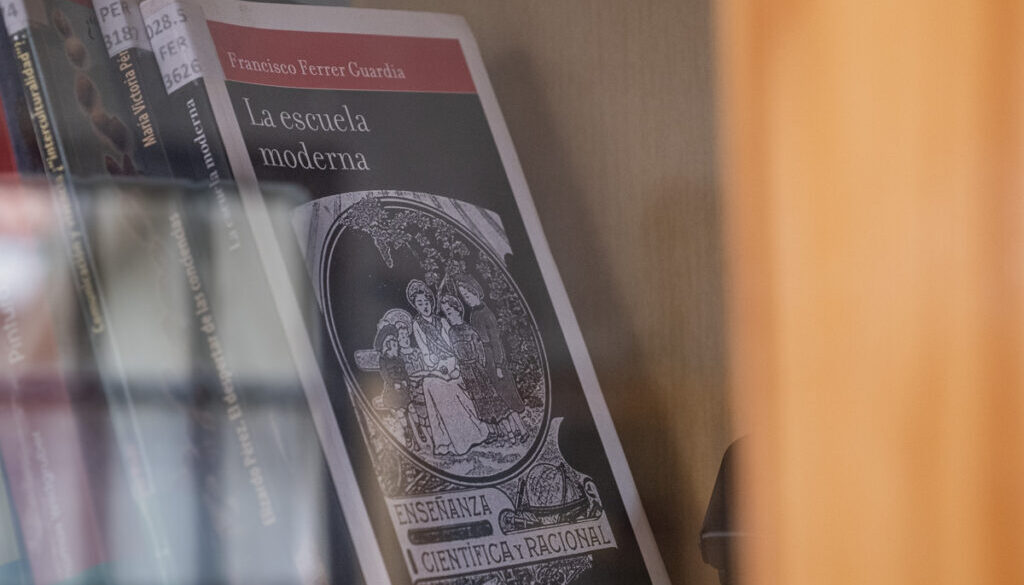

Writing in the 1960s, the Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire is best known for his visceral critique of our industrial models of education. With their focus on individual learning by rote, such models are well suited for conformity and repetitive labour, but hardly appropriate for today’s complexities. There’s a reason why many of the world’s greatest inventors and entrepreneurs either failed or dropped out of school. Freire’s major work, The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, is just as relevant today reminding us that if we want societies based on inclusion, ones that can draw on the creative talents of all, we need to radically rethink our education models. Greater participation in politics, so necessary in rebalancing inequalities, will merely replicate the same power imbalances unless citizens are taught to think for themselves as well as of each other. In a world where individuals have access to more knowledge on their smartphone than contained in the entire library of Alexandria, we need to teach children how to learn, not what to learn. Following in the footsteps of Freire’s journey of political exile we leave Brazil for Bolivia.

In the Altiplano of the Andes, the Aymaran philosophy of Suma Qamaña (broadly translated as ‘living well’) is inspiring an altogether different framework. Here the subject of happiness is not the individual, but instead the individual within the context of their community and their environment. For democracy to work we need individuals who can combine the critical thinking of the head with the empathy of the heart. The ability to ‘connect the dots’ as well as connect with others.

In the valleys below La Paz, we walk through the yard of the Kurmi Wasi school with teacher Marisa Barrientos. She sums up the approach that they practice here, ’we use a model of hacer-sentir-pensar (doing-feeling-thinking). Always in that order. This is where independence and responsibility come from’. Rather than ritualistic passages of information, education is self-directed as students play, explore, socialise and work together. The focus is on both the inter-relations and the autonomy of students to cultivate genuine forms of creativity, exchange and learning. Students design their own work plan against which they can measure their progress with the help of teachers, daily ‘rondas’and weekly student-teacher assemblies foster a sense of shared governance, and the Andean practice of ‘Apthapi’ encourages student-community engagement through the sharing of, ideas and knowledge. As one former student astutely stated, ‘true education can never be pumped in, on the contrary, it comes from the spontaneous flow, from the inside to out’.

In the classroom and at home, Kurmi Wasi’s children frequently supplement their learning with the vast depository of knowledge now available to them online. Marisa may teach her students how to think critically for themselves, but as we leave, we wonder what sort of information these children are accessing. Education is one piece of the puzzle, but what stories and voices dominate in the global information economy, and how can we ensure that a democratic diversity of worldviews is available to curious minds?