Brexit Means Brexit

“Democracy is always a work in progress, it’s never an absolute idea or it would otherwise be a totalitarian ideology just like all the rest of them”.

José Mujica, President of Uruguay (2010–2015)

London, UK

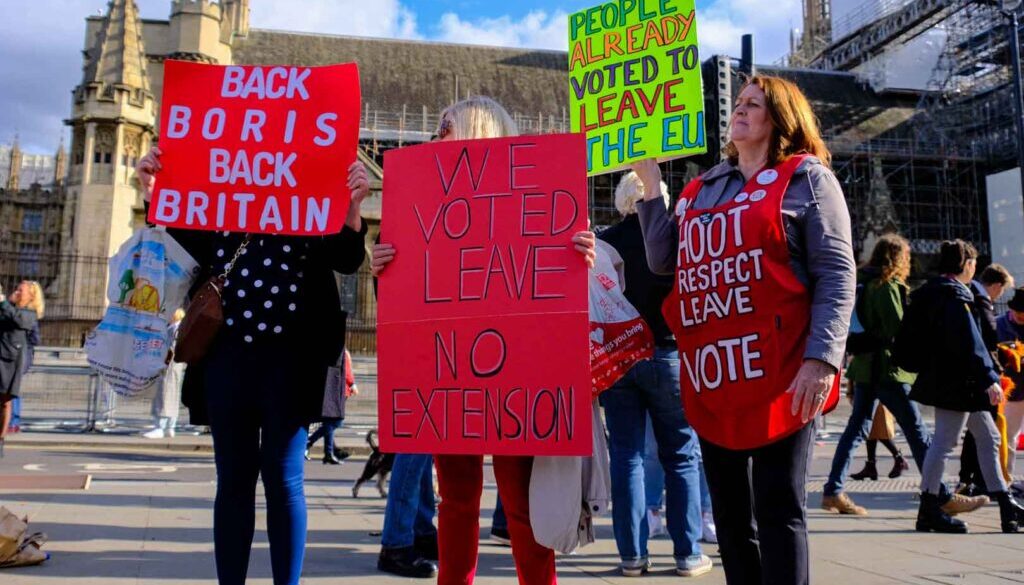

We begin our journey in the summer of 2019. Trump’s trade war with China shows no signs of letting up, civil protests are raging in Sudan, Hong Kong and Lebanon, Brexit has seemingly evolved into a political hydra beyond anyone’s control, and Britain has just come last in the Eurovision Song Contest. Again.

The UK seems at war with itself as the Brexit debate continues to expose long-standing grievances about class, race and wealth inequality. At the same time, the climate action group Extinction Rebellion is attempting to capture the flag in a desperate attempt to get politicians to sit up and pay attention to the arguably more pressing issue of the ecological crisis. In Parliament, democracy seems to be eating itself alive. Seen from the street, it seems a façade. And it’s not just here either. The US President is impulsively tweeting the fate of millions, Xi Jinping is crushing dissent from Xinjiang to Hong Kong, Viktor Orbán is making a mockery of the EU and Jair Bolsonaro looks on as the Amazon burns. As anger and disillusion with the status quo mounts, politics appears ever more hostile.

With impasse in Westminster and Extinction Rebellion’s ongoing rebellion on the street, there appears to be a clear juxtaposition between two forms of politics – one from above, one from below. One centralised, hierarchical, divided and competitive, the other crowd-sourced, distributed, collaborative and networked. Yet both are struggling to deal with the complexities and nuances of their respective challenges, in different ways and for different reasons.

Over the course of our lives, we had both been witness to many of the horrors of humanity in some of the worst conflict-affected countries in our previous lives as soldiers, journalists and aid workers. And the more we understood these problems, the more it seemed to come down to questions of inclusion and exclusion. Who was listened to and who was ignored, who had the power to decide and who was left out in the cold, angrily clutching onto a rusty but still deadly AK-47. The circulation of Soviet-manufactured weapons remains admittedly low in Britain, but the essential problem remains the same. Who’s at the table, and who’s not. The idea that the game ends here, that this is as far as humanity could go, just doesn’t cut it. Now isn’t the time to abandon democracy, but we also can’t continue along this path.

Is this the best that democracy can offer?

And what do we mean by democracy anyway? We throw the word around all the time but so rarely do we interrogate its deeper nature. Is a system of elections, representation by elites, party politics and so-called ‘liberal’ checks and balances really all that humanity can come up with, the ‘end of history’ as Francis Fukuyama infamously put it? We say that democracy and capitalism are the way to freedom. Yet while democracy says all citizens should have a voice, capitalism gives the rich by far the greater say. We say that democracy is rule by the people, yet like Plato, in our fear of the tyranny of the majority we instead create tyrannies of the minority. We say that democracy was born in Greece, yet the system we use today bears little resemblance to the way the ancient Athenians pursued politics. We say that democracy is a ‘western’ concept, yet can it be that the basic idea of discussing and collectively deciding our shared fate is somehow ‘western’, or indeed limited to any culture, geography or society? And can we really talk of a global crisis of democracy, when many in the world were never included in the conversation in the first place? Is democracy itself the problem, as the more cynical among us might begin to wonder, or is it rather the limited ways in which we currently understand what democracy is and could be?

None of which is to say that we need to tear everything down and start from scratch. Modernity and liberal democracy undoubtedly have their perks compared to some of the alternatives we’ve historically experienced. Nobody is suggesting we throw out the baby with the bathwater. This is about evolution, not revolution. So how might we combine the fruits of modernity, science, education and technology, with the deeper wisdom of our older instincts for solidarity, connection and interdependence to reforge democracy for our age? And where might we find inspiration for this new kind of politics?

We are certainly under no illusions that we are going to work it out by ourselves. This is a question that can only be answered with the same ethos that drove it – democratically, inclusively, open-mindedly and collectively. It’s a question that requires the input of people from all cultures, places, times and spaces.