Inequality and Protest in Spain: The Troubled Marriage Between Capitalism and Democracy

“We question this democracy because the parties in power do not look out for the collective good, but for the good of the rich. Excuses are not good enough for us. We do not want to choose between this existing democracy and the dictatorships of the past. We want a different life. Real democracy now!”

Beatriz García, an ‘indignada’ responding to being told ‘not to question democracy’ during the 2011 Madrid protests .

Madrid, Spain

July, 2019

The rate of income equality in Spain is one of the highest in Europe. And inequality gives rises to a simple question – if we truly live in democratic societies governed by popular consent, then how is it that such an unequal system has prevailed? Surely, if we all have an equal say in how our society is governed, then why would ‘the many’ allow ‘the few’ to accumulate so much wealth?

Europe’s second heatwave of the summer is in full swing, and while many Madrileños have already fled the heat to the coast for their annual vacation, a small group of anxious residents gather in a vacated, unventilated cafe in the east of the city. Luis González, himself a former banker turned community organiser, chairs the meeting of the ‘Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca’ (PAH) housing collective. He patiently listens as residents come forward to share their stories and seek advice. Many have been served eviction letters, and none present have been left untouched by Spain’s economic crisis. Evictions are common here, with over 6,000 cases reported in Madrid last year, and almost ten times that nationally. Just this morning, police forced their way through activists to evict a family including three children, while three days prior a woman threatened to throw herself out of a top-floor window in protest at her eviction notice. There’s a cruel irony here that 80% of these evictions have been carried out by Bankia, Spain’s fourth largest bank, which was itself bailed out by €24 billion of public money in 2008.

Income inequality here is some of the highest in Europe. How, in an affluent nation such as Spain, supposedly an advanced democracy, are people still struggling to secure their most basic human needs? Clearly, the problem is not one of a lack of resources. Not in a country that last year saw the creation of 7,000 new millionaires. Rather, the problem would seem to be one of effective distribution, arguably making it a moral, and by extension explicitly political question – yet one that is so often closed off to those most affected by it.

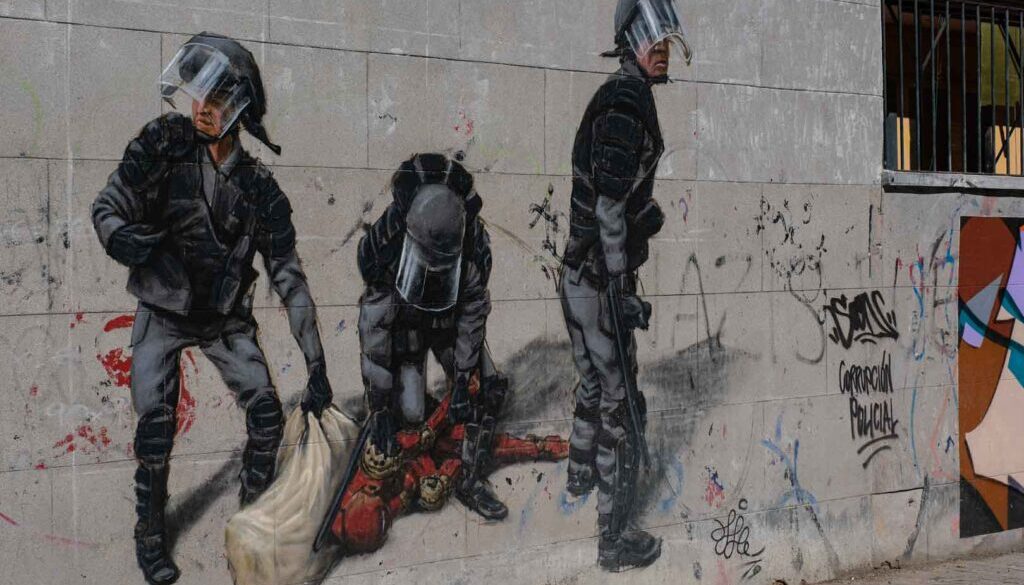

That same sense of indignation felt at the PAH meeting erupted on the streets back in 2011 – but what has become of it? Sitting on the terrace outside Achuri, a well-known leftist watering hole in the bohemian Lavapies district of Madrid, Juan Zarza explains that almost everyone here is a veteran of what he refers to as Spain’s ‘revolution’ – comparing it to the Arab Spring which began in the same year. An art photographer who felt compelled to leave his studio and use his camera to capture the unrest on the streets, he describes the collective feeling at the time. “Estábamos dormidos, ahora estamos despiertos [we were sleeping, now we are awake] – we used to say that a lot on the square, out on the streets, and I think it was a feeling many of us had, a feeling of a political awakening, of waking up to what was going on around us”. And yet, eight years later, Zarza and many others who fought with the police on the streets feel they have little to show for their efforts. The rise of Pablo Iglesias’ Podemos party off the back of the Indignados movement initially represented a beacon of hope for those seeking a more equal society. Yet their critics argue that once in government they got sucked into the system and rapidly lost touch with those who had fought hardest for change on the streets.

Both here and in Paris we saw just how hard it can be to force change from outside. But change from within doesn’t come easily either, as the experience of Podemos illustrates. Spain is just one example, and perhaps not even the worst at that, of democracy’s double bind. Without a measure of material equality in society, politics rapidly becomes a game that only a few can play. But without opening up politics, society remains materially unequal. It’s a vicious circle, and ultimately what this all seems to point us to was the idea that economic inequalities and political inequalities mutually define and reinforce each other. It’s the ‘Matthew effect’ all over again – money. makes money, power attracts power. Is it time to start thinking outside the box altogether?

Tired of the status quo, and dissatisfied with protests, others have tried to turn the problem on its head and approach it from a different angle by attempting to democratise the economy itself.

Nestled in the rolling hills of the Basque Country in northern Spain is the world’s largest worker-owned cooperative. In its 60 year existence, the Mondragon Corporation has grown to incorporate a network of 260 individual co-operatives, employing 75,000 people in Spain and internationally. Ander Etxeberria, who directs communications and runs educational tours for people from all over the world seeking to learn from the co-operative way of doing business explains that the salary ratio between the highest and lowest paid worker here is just 1:9. Compare that to 1:129 for the average FTSE 100 company. All of the Mondragon co-ops operate on a ‘one worker, one vote’ system, with a variety of formal and informal ways for workers to collectively decide the future of their jointly-owned enterprise. Wealth generated from the co-operatives is reinvested into collectively-owned schools, banks and healthcare.

Given the size and strength of the network, if one co-operative goes under, workers are absorbed by other co-ops in Mondragon, so people generally enjoy a much higher level of job security and the network as a whole is much more resilient to perennial market instability and shocks given this ethos of solidarity. Putting workers in charge also means that they take on more responsibility for the health of their co-operative, instead of adopting the more common and more individualistic ‘me vs the management’ approach, whereby workers push for higher salaries without thinking of the consequences for the business, and managers are less held to account. But if you’re thinking this sounds like something akin to a Soviet collectivisation scheme, think again. Perhaps one of the most interesting things about Mondragon, is that it still remains one of Spain’s most competitive businesses, with annual revenue of over €12 billion. It suggests that equity doesn’t have to come at the cost of efficiency, and such an approach can be inclusive and profitable. Worker cooperatives are certainly not a new idea, and not without their problems, but if we are to address power imbalances in society, we clearly need a multidimensional approach that goes beyond the realm of traditional politics.

But while the Mondragon network is no doubt impressive, it remains very much the exception rather than the rule. And despite Spain’s attempted political ‘revolution’ a decade ago, the underlying issues of wealth inequality are still here, insidiously gnawing away at society. It doesn’t take long for material inequality to entrench itself as deeper social divisions. Europe has changed since 2011 but those same issues are now driving a reaction of an altogether different nature not so far away.